Economic Value of Craftsmanship

Lunar Logic turns 15 this year. It’s quite a spell in this line of business. If you look at such a time frame you can safely assume that throughout the time the company has changed significantly.

It’s the people who define what the organizational culture, and thus the company identity, is. From that perspective, it’s enough to look at how the Lunar lineup has changed to figure how much we evolved. Let’s just say that with an exception of Ewelina—our office manager—and Paul—the founder—there’s no one who has seen the whole history of the company. We have changed.

And yet there’s one trait that remained consistent throughout all these years. Craftsmanship. It would characterize Lunar Logic A.D. 2005. It would be the same at the time when I joined in 2012. It would be no different today.

Craftsmanship

I explain craftsmanship as an aspiration to take pride in the quality of the work we do and continuously getting better at what we do. A tongue in cheek validation of whether we are craftspeople is as follows: if we don’t hate the outputs of our work from a year ago, be it code, designs, or processes, we don’t learn fast enough.

I like this way of framing craftsmanship because it is generic. It doesn’t boil down to a notion of software craftsmanship, which was popularized throughout the last several years in the industry. I can perceive myself as a craftsperson as much as our software developers can.

It would be interesting to analyze why, despite some major events and changes, craftsmanship remained a shared value at Lunar Logic. It is, however, another story. For this one, it is enough to stress how important craftsmanship is for us right now.

Does it mean that we would always aspire to achieve the best quality the way we understand it at any given moment? After all, that’s what you could translate craftsmanship into. The answer is no. In other words, despite our aspiration, we would sometimes compromise on our quality standards. Why?

Quality as an Investment

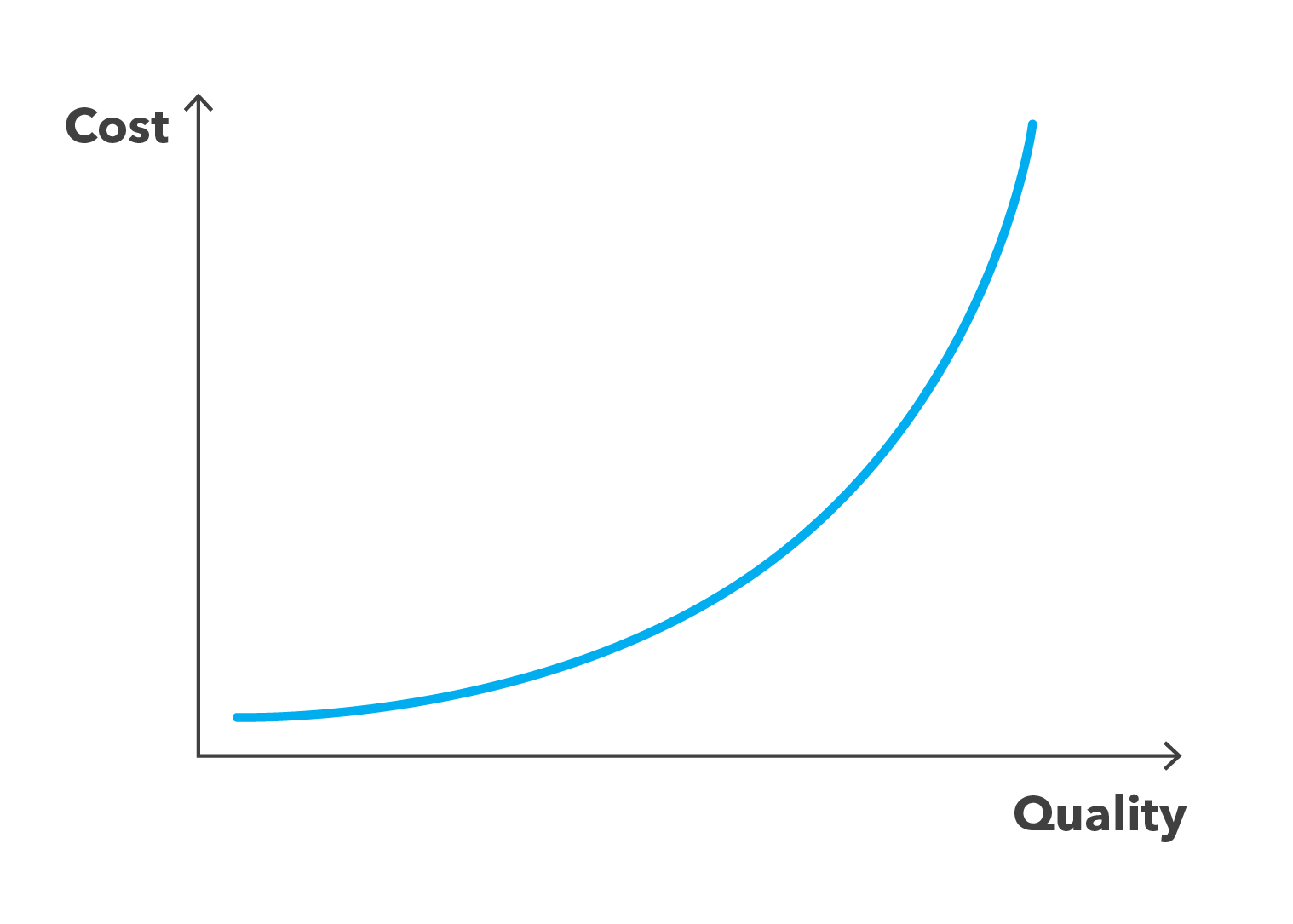

Let’s start with the assumption that embracing craftsmanship as an attitude translates into quality. Quality is an investment. It’s one side of a trade-off. The other side of it is time and effort. In other words, money. This investment is of diminishing returns. It means that the initial investment of some time and effort into quality will yield a better outcome than the following one that required similar time and effort. And that investment would bring a better outcome than another similar one.

In reverse, each similar increment in quality requires more time and effort, thus it costs more.

Couple that observation with a definition of craftsmanship I offered at the beginning. It says that we continuously learn more, which means that our understanding of good quality gets deeper. Simultaneously, we aspire to produce quality work we are proud of. Over time, it would mean that we want our work to be of higher and higher quality. What follows is that we would introduce more cost.

The additional cost, to some extent, is offset with the gains we get from good quality work. If a product is buggy and unusable the cost investment in better quality would easily be compensated by additional value created by simply removing obstacles that prevent customers from using the product effectively. However, the better the product the smaller improvement of the value.

At some point, another investment in quality improvement would cost more than it would deliver value. By that time, further investment in quality isn’t economically sound anymore. And yet, being craftspeople, we want to move the quality needle indefinitely. Inevitably we are bound to reach the point where our craftsmanship can’t be economically justified anymore.

Too Much Craftsmanship?

That’s probably the most important lesson of our craftsmanship journey. When we build a product for a customer, we set craftsmanship in the economic context. How much quality can be justified in a given situation?

The answer almost never is “as much as possible”. We work extensively with early-stage startups. In such scenarios, the key value we can provide is an opportunity to validate, or more likely invalidate the idea. There’s obviously some level of quality that is required for people to try a product so that they can provide meaningful feedback. How much more effort invested in high quality can be rationally justified, though?

It is a rare case that very high technical standards are a prerequisite to validating the product market fit. It would be true for scaling. It would be true for rapid and continuous development. It wouldn’t be so when the goal is to put the product out there for early adopters to try it and share their feedback.

Craftsmanship as Economical Trade-off

This means that, more often than not, we constrain ourselves in our pursuit of craftsmanship when we are working on commercial gigs. We would go only as far as we can economically justify to our clients.

By the way, it is different when we do some work internally, e.g. when working on internal projects during slack time. We often use these opportunities to hone our skills, thus attempt to deliver the best possible quality. In such a case the goal is not the product but the learning process thus the economic equation is completely different. It does, however, give us a good understanding of the cost side of pursuing very high standards of quality. Through that, we make better decisions when working with our clients.

One thing remains the same, though. If we decide to look at such code or design in a year from now we’ll hate it. After all, that’s what craftsmanship is all about.